We've previously looked at a few signatures on the signs that were perhaps left by those who painted and maintained them. Signs typically require regular maintenance whether neon or more modern LED displays. Sign companies often monitor the landscape and send out workers to check for burned out lights or other issues so they can later be repaired.

Written by

But what was it really like to work on the signs? Workers’ experiences have been documented to some extent, though more research and oral histories are needed. Here are just a few anecdotes and historical accounts.

A common theme in the stories of sign maintenance workers is that the job can be a bit of a challenge and is likely not the best career choice for those scared of heights.

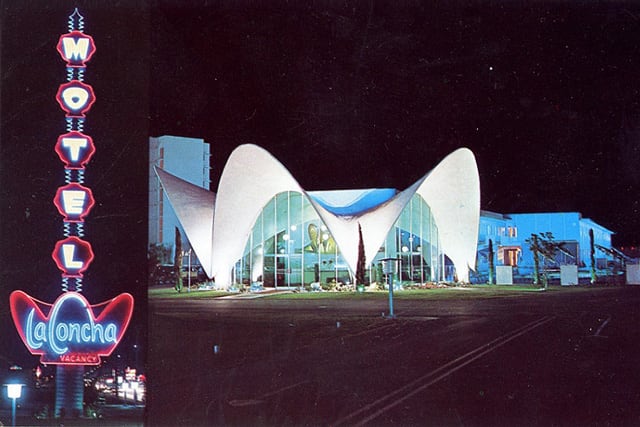

Visitors to the museum often hear about the maintenance rungs on the c. 1961 La Concha Motel sign. Climbing up on the top rungs of the letter M would have meant you were up nearly eight stories high without any safety harnesses. This would have been the case before the 1970s, according to YESCO’s Steve Weeks (which perhaps not coincidentally was the period in which OSHA was created). Now workers use equipment such as harnesses, lifts, and cranes.

Postcard image of the La Concha Motel. Anthony Bondi Collection, The Neon Museum.

The surviving MOT letters and the “La Concha” section of the sign are on display in the Neon Boneyard. The lobby building by architect Paul Revere Williams is now the museum’s visitors’ center.

Another sign at the museum featuring rungs like these is from the Showboat.

The Showboat Hotel and Casino opened on East Fremont Street in 1954. The roadside sign tower featuring these letters was added in the early 1960s. The letters themselves are approximately 15 feet tall, but they were originally high up on the sign which may have made the maintenance very complicated to maneuver. Many of the letters are on display in the Neon Boneyard and North Gallery.

1970s postcard image. Anthony Bondi Collection, The Neon Museum.

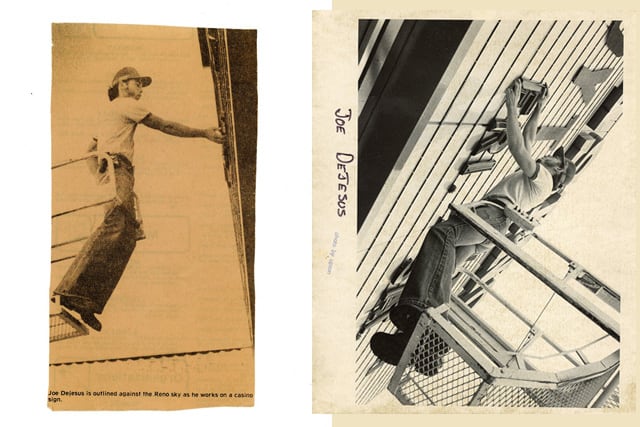

A few years back sign industry veteran Joe DeJesus generously permitted the museum to scan photos and images of items from his career, including some scrapbook material. DeJesus started his sign career sweeping floors at a sign shop as a teenager before working his way up to a senior position at Ad-Art and other major companies.

Several photos and clippings show DeJesus and colleagues at work using lifts to change bulbs or readerboard letters.

Undated images from a job in Reno, Joe DeJesus Collection, The Neon Museum:

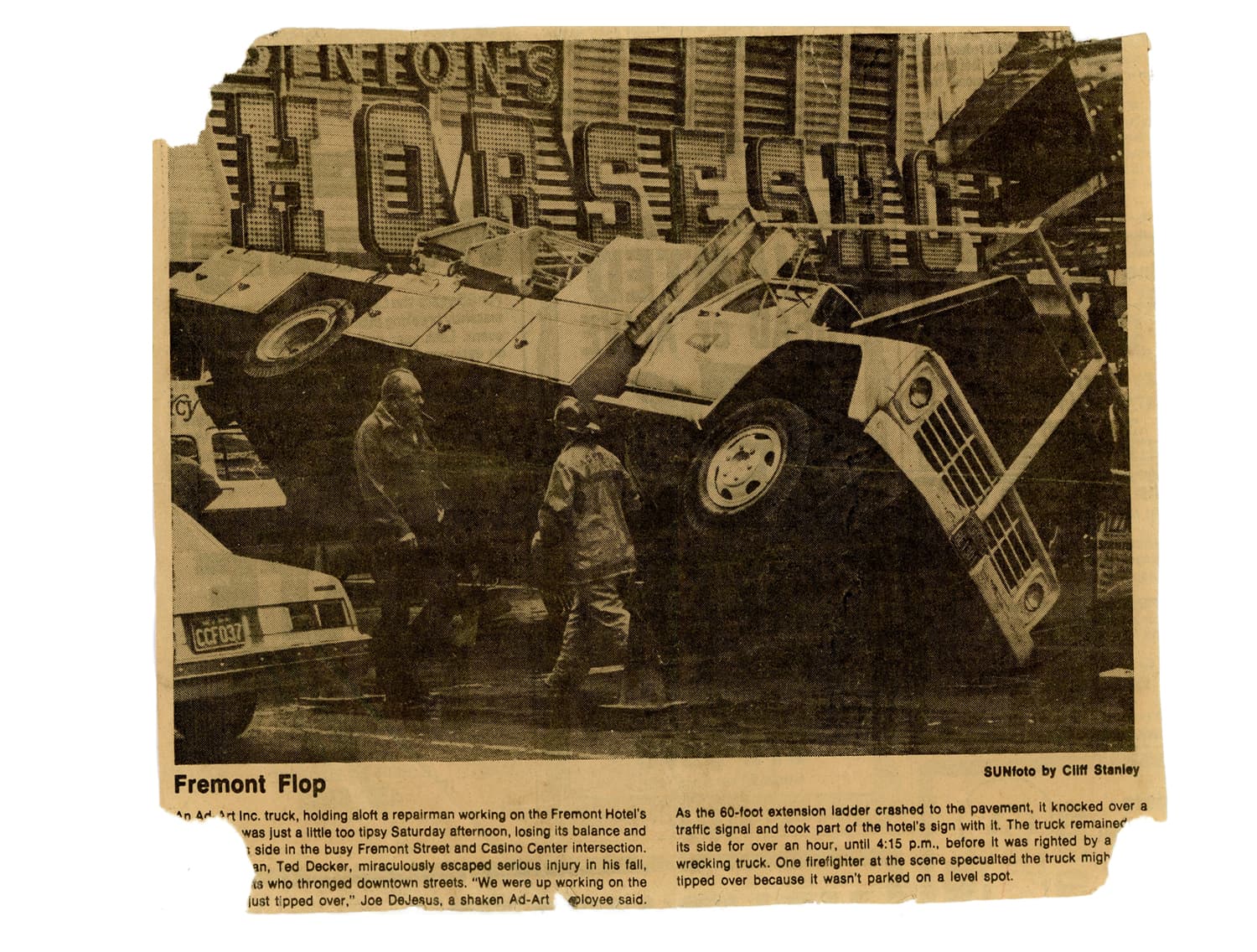

A couple of newspaper clippings from 1978 also show the potential hazards of the job when it came to sign maintenance. Joe DeJesus Collection, The Neon Museum.

DeJesus and fellow Ad-Art worker Ted Decker luckily came out of this accident without major injuries after their truck and crane tipped over on Fremont Street.

These challenges are seen in a couple more accounts.

Architect and scholar Stefan Al brought to light the story of Daniel Kempf back in his Neon Museum scholar in residence lecture in 2016 and later in his book The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream. Al reported that YESCO’s Las Vegas crews changed a quarter of a million bulbs in 1985. Daniel Kempf was said to be one of the best and was quoted as saying “I get shocked all of the time” and that it is “better than a morning cup of coffee.” Recalling a time he had to climb into Circus Circus’ “Lucky the Clown” in the hot Las Vegas weather, Kempf described the heat inside the signs as “enough to melt the socks right off you.” He would regularly go on two-hour patrols at night with a tape recorder in hand, looking for blacked out lights. Kempf did concede that he was involved in a few accidents while driving around in search of dead bulbs. Al also noted that at one point, Kempf suffered a 50-foot fall from the Tropicana sign “tearing his ligaments and shattering his teeth.”

A more recent account is that of Mario Basurto from the 1990s. He worked for YESCO conducting maintenance on the Fremont Street Experience and echoed the challenges described by Kempf while touching on other facets of the job. His reflections were first made available as part of a series of photos and casino worker profiles by Kit Miller in the mid-90s that were later published in 2002 as part of The Grit Beneath the Glitter: Tales from the Real Las Vegas.

Basurto was relatively new, having worked for YESCO for six months. He pointed out the risk of electric shock while going 110 feet up in a lift to change out lights and run tests on the Fremont Street Experience canopy. The 11 p.m. - 7 a.m. graveyard shift took time to adjust to and a toll on his social life. As an apprentice, he made eleven dollars an hour, noting that that was “half of what a journeyman makes.” Basurto said that he would soon switch back to the day shift and that “I’ll be working on all kinds of signs, changing neon and fluorescent lights, for banks, casinos, tennis courts. I like the work. I put my mind to it, and I learn all I can from these guys. They take the time to teach me.”

The history of the sign profession in Las Vegas has tended to overlook the roles of women in an industry that has been largely dominated by men (of course with some exceptions such as designers Betty Willis and Marge Williams and, more recently, Ina Macias of Paul’s Neon Signs).

Local historian and reporter Tom Hawley recently highlighted the story of Blanche Linford, who also conducted a “sign patrol” to look for dimmed or burned out lights. A local news story from 1985 reported that Linford (apparently misspelled Lenford in the story) worked for twenty years doing this work, two nights each week for a few hours. This appears to have been her primary responsibility with Linford stating that as a result “tourists come to Las Vegas and they see things in working order.” In this instance, she brought her daughter along for the ride to record signs that needed work. The reporter, News 3’s Darwin Morgan, informed viewers that “Blanche’s husband is the owner of a local sign company” and that they have contracts with many of the casinos. The company and her husband go unnamed leaving the full story here a bit murky. However, the husband likely referred to in the story is Richard Linford who worked for YESCO as a service manager in the 1980s and later had his own company called Linford Electric Sign & Maintenance Company, Inc.

The rungs on the La Concha Motel sign and others at The Neon Museum thus serve as reminders of the work it took and still takes to keep the signs running. We hope to delve deeper and spotlight more of these and other Las Vegas workers’ stories in the future. Do you have any memories, photos, or anything else you’d like to share? We’d love to hear from you. Please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.